GlobalWolfStreet

@t_GlobalWolfStreet

What symbols does the trader recommend buying?

Purchase History

Trader Messages

Filter

Message Type

Understanding Cross-Border Payments At its core, a cross-border payment occurs when the payer and the recipient are located in different countries and the transaction involves at least two different currencies or financial systems. Examples include an Indian exporter receiving payment from a US buyer, a migrant worker sending money to family back home, or a multinational company paying overseas suppliers. Unlike domestic payments, cross-border payments must navigate differences in currencies, banking regulations, time zones, compliance standards, and settlement systems. This makes them slower, costlier, and more complicated than local transactions. How Cross-Border Payments Work Traditional cross-border payments are typically processed through correspondent banking networks. In this system, banks maintain relationships with foreign banks (correspondent banks) to facilitate international transfers. When a payment is initiated, it may pass through multiple intermediary banks before reaching the final beneficiary. Each intermediary charges a fee and adds processing time. The SWIFT (Society for Worldwide Interbank Financial Telecommunication) network plays a major role by providing secure messaging between banks. However, SWIFT itself does not move money; it only sends payment instructions. Actual fund settlement happens through bank accounts held across borders. In recent years, alternative mechanisms have emerged, including fintech platforms, digital wallets, and blockchain-based systems, which aim to simplify and speed up cross-border transfers. Key Participants in Cross-Border Payments Several entities are involved in the cross-border payment ecosystem: Banks and Financial Institutions: Provide traditional wire transfers and trade finance services. Payment Service Providers (PSPs): Companies like PayPal, Wise, and Stripe offer faster and more transparent international payments. Central Banks: Regulate currency flows and oversee payment systems. Clearing and Settlement Systems: Ensure final transfer of funds between institutions. Businesses and Individuals: End users such as exporters, importers, freelancers, students, and migrant workers. Costs and Fees in Cross-Border Payments One of the biggest challenges in cross-border payments is cost. Fees may include: Transfer fees charged by banks or PSPs Currency conversion or foreign exchange (FX) margins Intermediary bank charges Compliance and documentation costs For small-value transactions like remittances, these costs can be disproportionately high. Reducing fees has become a global priority, especially for developing economies where remittances are a major source of income. Speed and Transparency Issues Traditional cross-border payments can take anywhere from one to five business days to settle. Delays occur due to manual processing, time zone differences, compliance checks, and multiple intermediaries. Additionally, senders often lack transparency on where their money is during the transfer process and what total fees will be deducted. Modern digital payment platforms are addressing these issues by offering near real-time transfers, upfront fee disclosure, and end-to-end tracking. Regulatory and Compliance Challenges Cross-border payments are subject to strict regulatory requirements, including anti-money laundering (AML), combating the financing of terrorism (CFT), and know-your-customer (KYC) rules. Each country has its own regulatory framework, which can create friction and increase compliance costs. Sanctions, capital controls, and geopolitical tensions further complicate cross-border transactions. Financial institutions must continuously monitor regulatory changes to avoid penalties and ensure smooth operations. Role of Technology in Cross-Border Payments Technology is transforming the cross-border payments landscape. Fintech innovations are reducing reliance on correspondent banking and improving efficiency. Key technological trends include: Blockchain and Distributed Ledger Technology (DLT): Enables faster settlement and reduced intermediaries. Application Programming Interfaces (APIs): Allow seamless integration between payment systems. Real-Time Payment Networks: Enable instant or near-instant transfers across borders. Artificial Intelligence (AI): Enhances fraud detection and compliance monitoring. These innovations are making cross-border payments more accessible, especially for small businesses and individuals. Cross-Border Payments and Global Trade International trade depends heavily on efficient cross-border payment systems. Exporters need timely payments to manage cash flows, while importers seek secure and cost-effective settlement options. Trade finance instruments such as letters of credit, bank guarantees, and documentary collections are closely linked to cross-border payment mechanisms. Efficient payment systems reduce transaction risks, improve trust between trading partners, and support global supply chains. Importance of Cross-Border Remittances Remittances are one of the most significant components of cross-border payments, particularly for emerging economies. Millions of migrant workers send money home regularly to support families, education, healthcare, and housing. These flows contribute significantly to national income and economic stability. Improving the affordability and speed of remittance services can have a direct positive impact on financial inclusion and poverty reduction. The Future of Cross-Border Payments The future of cross-border payments is moving toward greater speed, lower cost, and enhanced transparency. Central bank digital currencies (CBDCs), global payment interoperability, and standardized compliance frameworks are expected to play a major role. Collaboration between banks, fintech firms, regulators, and international organizations will be crucial in building efficient global payment infrastructure. As technology evolves, cross-border payments are likely to become as seamless as domestic transactions. Conclusion Cross-border payments are a vital pillar of the global financial system, enabling trade, investment, and personal financial connections across nations. While traditional systems face challenges related to cost, speed, and complexity, technological innovation and regulatory cooperation are driving meaningful improvements. As the world becomes more interconnected, efficient and inclusive cross-border payment systems will be essential for sustainable global economic growth.

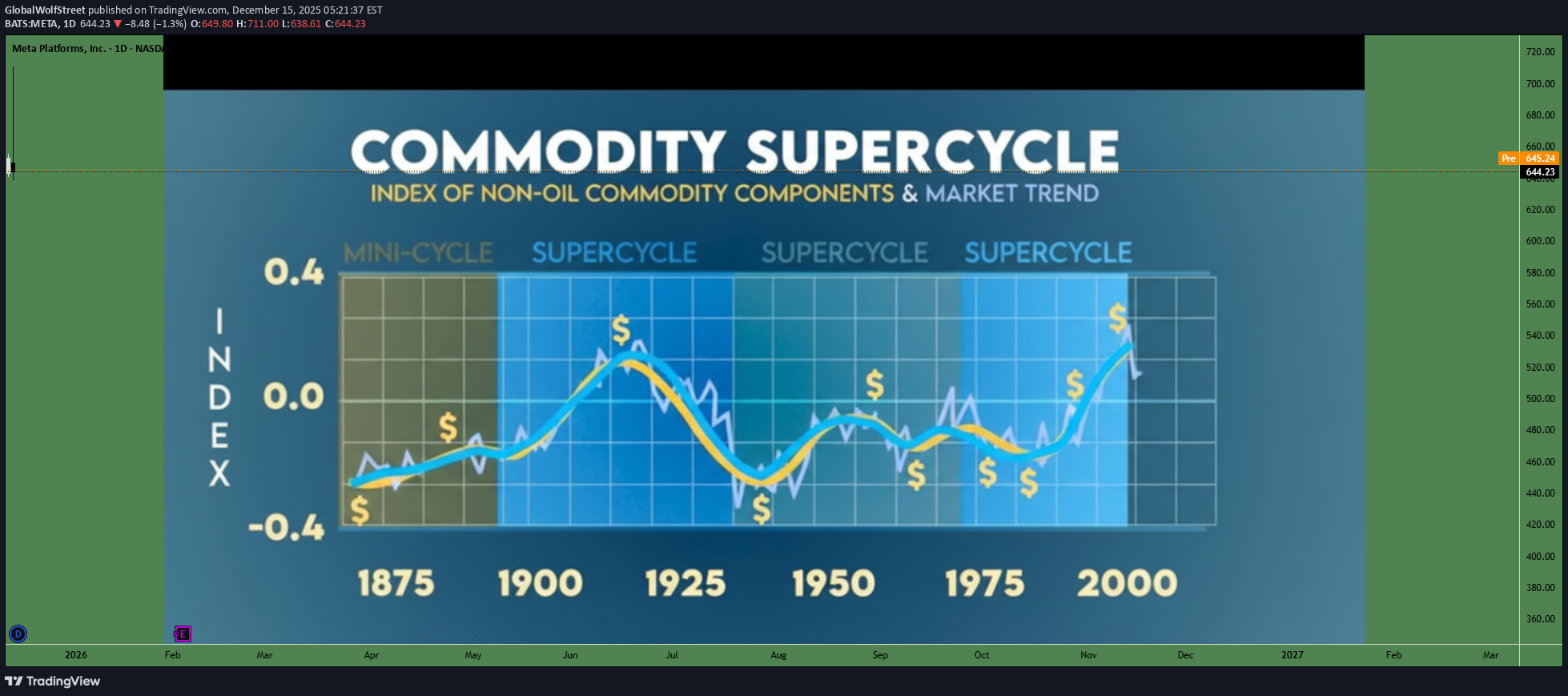

Understanding the Long-Term Boom and Bust of Global Resources A commodity super cycle refers to a prolonged period—often lasting a decade or more—during which commodity prices rise significantly above their long-term average, driven by strong and sustained demand growth. Unlike short-term commodity rallies caused by temporary supply disruptions or speculative activity, a super cycle is structural in nature. It is usually powered by major global economic transformations such as industrialization, urbanization, technological shifts, demographic changes, or large-scale infrastructure development. Historically, commodity super cycles have played a crucial role in shaping global economies, influencing inflation, trade balances, corporate profits, and investment flows. Understanding the dynamics of a commodity super cycle helps investors, policymakers, businesses, and traders prepare for both opportunities and risks across commodities such as metals, energy, agriculture, and industrial raw materials. Origins and Concept of a Commodity Super Cycle The concept of a commodity super cycle gained prominence through the work of economists who observed long-term price trends across commodities. They noticed that commodity prices tend to move in extended waves rather than random patterns. These cycles typically consist of four phases: early recovery, expansion, peak, and decline. Super cycles are not driven by speculation alone. They emerge when demand consistently outpaces supply for many years. Since commodity production requires heavy capital investment and long lead times—mines, oil fields, pipelines, and farms cannot be expanded overnight—supply often struggles to respond quickly, pushing prices higher for extended periods. Key Drivers of a Commodity Super Cycle Rapid Economic Growth and Industrialization One of the strongest drivers of a super cycle is rapid economic growth in large economies. For example, the industrialization of the United States in the early 20th century and China’s economic expansion from the early 2000s created massive demand for steel, copper, coal, oil, and cement. Urbanization increases consumption of metals, energy, and construction materials on an unprecedented scale. Infrastructure and Urban Development Large infrastructure programs—roads, railways, ports, power plants, housing, and smart cities—require enormous quantities of commodities. When governments invest heavily in infrastructure over long periods, it creates sustained demand that supports a super cycle. Demographic Shifts and Population Growth Growing populations and rising middle classes increase demand for food, energy, housing, transportation, and consumer goods. Agricultural commodities, energy products, and industrial metals all benefit from these structural changes. Technological and Energy Transitions New technologies can trigger commodity demand shocks. The current global shift toward renewable energy, electric vehicles, and decarbonization has increased demand for lithium, copper, nickel, cobalt, and rare earth elements. Such transitions can spark new commodity super cycles focused on “green” or strategic metals. Supply Constraints and Underinvestment Commodity markets are cyclical, and long periods of low prices often lead to underinvestment. When demand later accelerates, limited supply capacity causes prices to surge. Environmental regulations, geopolitical tensions, and resource depletion further constrain supply, amplifying the cycle. Historical Examples of Commodity Super Cycles Early 20th Century (1890s–1920s): Driven by industrialization in the US and Europe, fueling demand for coal, steel, and agricultural commodities. Post–World War II Boom (1945–1970s): Reconstruction of Europe and Japan, combined with population growth, led to strong commodity demand. China-Led Super Cycle (2000–2014): China’s rapid industrial growth and urbanization created one of the largest commodity booms in history, pushing prices of iron ore, copper, oil, and coal to record highs. Each cycle eventually ended as supply caught up, demand slowed, or economic conditions changed. Impact on Global Economies Commodity super cycles have profound macroeconomic effects: Inflation: Rising commodity prices increase production and transportation costs, often leading to higher consumer inflation. Exporters vs Importers: Commodity-exporting countries (such as Australia, Brazil, Russia, and Middle Eastern nations) benefit from improved trade balances and economic growth, while importing nations face higher costs. Currency Movements: Exporters’ currencies often strengthen during a super cycle, while importers may see currency pressure. Corporate Profits and Investment: Mining, energy, and commodity-linked companies experience higher revenues and profits, encouraging capital investment and mergers. Role of Financial Markets and Investors For investors, a commodity super cycle creates long-term opportunities across asset classes: Equities: Mining, energy, fertilizer, and infrastructure companies often outperform. Commodities and Futures: Direct exposure through futures, ETFs, and commodity indices becomes attractive. Inflation Hedges: Commodities are often used to hedge against inflation during super cycles. Emerging Markets: Resource-rich emerging economies tend to attract capital inflows. However, volatility remains high, and timing is critical, as late-cycle investments can suffer sharp corrections. Risks and Limitations of a Super Cycle Despite their long duration, commodity super cycles are not permanent. Risks include: Overcapacity: High prices encourage excessive supply expansion, eventually leading to oversupply. Technological Substitution: Innovation can reduce reliance on certain commodities, lowering demand. Economic Slowdowns: Recessions or financial crises can abruptly end demand growth. Policy and Environmental Constraints: Climate policies and regulations can both boost and restrict commodity demand, creating uncertainty. Investors and policymakers must recognize that every super cycle eventually peaks and reverses. Is the World Entering a New Commodity Super Cycle? Many analysts believe the global economy may be entering a new commodity super cycle driven by energy transition, infrastructure spending, supply chain reshoring, and geopolitical fragmentation. Metals critical for clean energy, food security concerns, and constrained fossil fuel investment are all contributing factors. However, whether this develops into a full super cycle depends on sustained global growth, policy consistency, and long-term demand trends. Conclusion A commodity super cycle represents a powerful and transformative phase in the global economy, marked by prolonged periods of rising commodity prices driven by structural demand shifts and supply constraints. These cycles reshape industries, influence inflation, alter trade dynamics, and create significant investment opportunities—while also carrying substantial risks. Understanding the causes, phases, and impacts of a commodity super cycle allows market participants to make informed decisions and better navigate the long-term ebb and flow of global commodity markets.

Shipping as the Engine of Global Trade At its core, shipping facilitates international trade by transporting goods between countries and regions. Nations differ in natural resources, labor skills, technology, and capital availability. Shipping allows countries to specialize in what they produce most efficiently and trade with others, following the principle of comparative advantage. For example, crude oil from the Middle East, iron ore from Australia, manufactured electronics from East Asia, and agricultural products from South America all move across oceans through shipping networks. This exchange promotes productivity, lowers costs, and increases the variety of goods available to consumers worldwide. Shipping also enables large-scale trade that would be impossible through air or land transport alone. Bulk carriers transport coal, grain, and minerals in massive volumes at low cost, while container ships move manufactured goods efficiently through standardized containers. Tankers carry oil, liquefied natural gas (LNG), and chemicals, supporting global energy markets. Each shipping segment serves a specific economic purpose, together forming an integrated system that sustains the world market. Impact on Global Supply Chains Modern supply chains are highly complex and international in nature, relying heavily on shipping. Many products are no longer made in a single country; instead, components are sourced from multiple regions and assembled elsewhere. Shipping ensures the smooth flow of intermediate goods and raw materials between production stages. Just-in-time manufacturing, widely used in industries such as automobiles and electronics, depends on predictable and timely shipping schedules. Disruptions in shipping—such as port congestion, geopolitical conflicts, pandemics, or canal blockages—can have immediate and widespread effects on global markets. Delays increase costs, reduce availability of goods, and contribute to inflation. The COVID-19 pandemic highlighted how critical shipping is, as container shortages and freight rate spikes affected everything from food prices to industrial production. This demonstrated that shipping is not merely a logistical function but a strategic pillar of global economic stability. Role in Price Formation and Inflation Shipping costs directly influence global prices. Freight rates are a significant component of the final cost of many goods, especially commodities and low-value, high-volume products. When shipping costs rise due to fuel price increases, regulatory changes, or supply-demand imbalances, these higher costs are often passed on to consumers, contributing to inflation. Conversely, efficient shipping and lower freight rates help keep prices competitive and affordable. Shipping also plays a role in commodity price discovery and arbitrage. The ability to transport goods between markets allows traders to exploit price differences across regions, which eventually leads to price convergence. For instance, grain or crude oil can be shipped from surplus regions to deficit regions, stabilizing global prices and reducing extreme volatility. Strategic and Geopolitical Importance Shipping is closely linked to geopolitics and national security. Major sea routes such as the Strait of Hormuz, the Suez Canal, the Panama Canal, and the South China Sea are critical chokepoints for global trade. Any disruption in these routes—due to conflicts, sanctions, or political tensions—can have serious consequences for the world market. Countries often seek to secure maritime routes and ports to protect their trade interests and energy supplies. Shipping is also affected by international sanctions and trade policies. Restrictions on shipping insurance, port access, or vessel movements can limit a country’s ability to trade, impacting global supply and prices. As a result, shipping companies, insurers, and governments must constantly assess geopolitical risks when operating in international markets. Economic Growth and Employment The shipping industry contributes significantly to global economic growth and employment. It supports millions of jobs worldwide, including seafarers, port workers, shipbuilders, logistics professionals, and maritime service providers. Ports act as economic hubs, attracting industries such as manufacturing, warehousing, and transportation. For developing countries, access to efficient shipping services is essential for integrating into global trade and achieving export-led growth. Shipping also enables small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) to participate in international markets. Containerization and digital logistics platforms have reduced barriers to entry, allowing businesses to ship goods globally without owning vessels or large infrastructure. Technological Advancements and Digitalization Technological innovation is transforming the shipping industry and enhancing its role in the world market. Containerization revolutionized trade in the 20th century by reducing loading times and costs. Today, digitalization, automation, and data analytics are improving efficiency, transparency, and reliability. Technologies such as blockchain, electronic bills of lading, and real-time vessel tracking help reduce delays, fraud, and administrative costs. Automation in ports and the development of smart ships are further strengthening global trade flows. These advancements allow shipping to handle growing trade volumes while maintaining cost efficiency, which is vital for sustaining global economic expansion. Environmental and Sustainability Considerations As shipping underpins global trade, it also faces increasing scrutiny over its environmental impact. The industry contributes to greenhouse gas emissions and marine pollution. In response, international regulations and market pressures are pushing shipping toward cleaner fuels, energy-efficient vessels, and sustainable practices. Although environmental compliance may increase short-term costs, it supports long-term stability by aligning shipping with global climate goals and ensuring its continued role in the world market. Conclusion The role of shipping in the world market is fundamental and multifaceted. It enables global trade, supports supply chains, influences prices and inflation, and plays a strategic role in geopolitics and economic development. Shipping connects nations, markets, and people, making globalization possible. While the industry faces challenges such as geopolitical risks, environmental pressures, and market volatility, its importance continues to grow alongside international trade. A resilient, efficient, and sustainable shipping sector is essential for the smooth functioning and future growth of the world market.

A High-Speed Trading Strategy in a Globalized Financial System Scalping in the world market is a short-term trading strategy that focuses on capturing very small price movements across global financial instruments. It is one of the fastest and most execution-intensive styles of trading, relying on high liquidity, tight bid-ask spreads, and rapid decision-making. In today’s interconnected global financial system—where markets operate nearly 24 hours a day across regions like Asia, Europe, and North America—scalping has evolved into a sophisticated discipline practiced by both individual traders and institutional participants. At its core, scalping aims to profit from minor inefficiencies in price rather than large directional moves. A scalper may enter and exit dozens or even hundreds of trades in a single trading session, holding positions for seconds or minutes. While individual profits per trade are small, the cumulative gains can be significant when combined with discipline, consistency, and strict risk control. Global Market Structure and Scalping Opportunities The global market environment provides a continuous flow of opportunities for scalpers. As trading sessions move from Tokyo to London to New York, liquidity and volatility shift across asset classes. For example, Asian hours often see higher activity in Japanese yen pairs, while European sessions dominate euro and pound-based instruments. The overlap between London and New York sessions is particularly attractive for scalping due to increased volume, tighter spreads, and faster price movements. Scalping is commonly applied in global forex markets, index futures, commodities like gold and crude oil, cryptocurrencies, and highly liquid equities. Forex markets are especially popular because of their deep liquidity and round-the-clock access. Similarly, global index derivatives such as the S&P 500, DAX, FTSE, and Nikkei offer sharp intraday movements ideal for short-term strategies. Key Characteristics of Scalping in World Markets Scalping in global markets is defined by speed, precision, and consistency. Traders rely heavily on real-time data, low-latency trading platforms, and reliable execution. Because price changes are small, transaction costs such as spreads, commissions, and slippage play a critical role in profitability. Successful scalpers choose instruments with minimal spreads and high trading volume to reduce friction. Another defining feature is the use of lower time frames, typically ranging from tick charts to one-minute or five-minute charts. These short intervals allow traders to identify micro-trends, breakouts, and momentum bursts that occur frequently throughout the trading day. Scalpers are less concerned with long-term fundamentals and more focused on immediate supply-demand imbalances. Tools and Techniques Used by Global Scalpers Scalpers in world markets depend on technical analysis rather than macroeconomic forecasting. Popular tools include moving averages, volume indicators, VWAP (Volume Weighted Average Price), RSI, stochastic oscillators, and order-flow analysis. Many traders watch price action closely, focusing on support and resistance levels, market depth, and candlestick behavior. News awareness is also essential. While scalpers do not trade long-term fundamentals, global economic releases—such as interest rate decisions, inflation data, employment reports, or geopolitical announcements—can create sudden spikes in volatility. During such events, spreads may widen and execution may become difficult, prompting many scalpers to either adapt their strategies or stay out of the market temporarily. Risk Management in High-Frequency Trading Risk management is the backbone of scalping in global markets. Because the frequency of trades is high, even a small lapse in discipline can lead to rapid losses. Scalpers typically use very tight stop-loss orders and predefined profit targets. The risk-to-reward ratio per trade may appear modest, but consistency and win rate compensate over time. Position sizing is carefully calculated to ensure that no single trade can significantly damage the trading account. Many professional scalpers risk only a small fraction of their capital on each trade, focusing on protecting capital first and profits second. Emotional control is equally important, as rapid trading can amplify stress and lead to impulsive decisions. Technology and the Evolution of Scalping Advancements in trading technology have transformed scalping in world markets. High-speed internet, advanced charting software, algorithmic trading systems, and direct market access have improved execution quality and reduced latency. Institutional players often use automated or semi-automated strategies to scalp price differences across exchanges and instruments. Retail traders, while not competing directly with large institutions on speed, still benefit from modern platforms that offer real-time quotes, one-click trading, and advanced analytics. However, this also means competition is intense, and success requires continuous learning and adaptation to changing market conditions. Psychological Demands of Global Scalping Scalping is mentally demanding. Traders must maintain focus for extended periods, react quickly to changing conditions, and accept frequent small wins and losses without emotional attachment. Overtrading, fatigue, and revenge trading are common pitfalls, especially in fast-moving global markets. Successful scalpers develop a structured routine, including defined trading hours, clear entry and exit rules, and regular performance reviews. They understand that not every day will be profitable and that discipline over hundreds of trades matters more than any single outcome. Advantages and Limitations of Scalping Worldwide The primary advantage of scalping in world markets is the abundance of opportunities. With multiple global sessions and asset classes, traders can find setups almost any time of day. Scalping also reduces overnight risk since positions are closed quickly. However, the strategy is not suitable for everyone. High transaction costs, intense concentration requirements, and technological dependency can be challenging. Regulatory differences across countries, leverage restrictions, and tax implications may also affect global scalpers, requiring careful planning and compliance. Conclusion Scalping in the world market represents the most dynamic and fast-paced form of trading in the global financial ecosystem. It thrives on liquidity, volatility, and precision, turning small price movements into consistent opportunities. While the potential rewards are attractive, success demands advanced technical skills, strict risk management, psychological discipline, and reliable technology. In an increasingly interconnected global market, scalping remains a powerful yet demanding strategy—best suited for traders who can master speed, control, and consistency in a constantly moving financial world.

1. Why Invest in Gold? Gold offers several compelling reasons for investment. Primarily, it acts as a hedge against inflation. During periods when the purchasing power of fiat currencies declines, gold prices generally rise, preserving wealth. For example, during the 1970s, the US experienced high inflation, and gold prices surged dramatically. Additionally, gold provides protection during economic and geopolitical uncertainty. In times of financial crises, such as the 2008 global recession, investors flocked to gold as a safe-haven asset. Gold is not tied to any single country’s economy, making it a globally recognized store of value. Diversification is another key reason. Financial advisors often suggest including gold in an investment portfolio to reduce overall risk. Unlike stocks or bonds, gold has a low or negative correlation with other asset classes, which means its value can remain stable or even rise when other investments falter. 2. Forms of Gold Investment Investors can access gold through various channels, each with unique advantages and considerations: Physical Gold: This includes gold bars, coins, and jewelry. Physical gold provides tangible ownership and a psychological sense of security. However, it requires safe storage and insurance, and liquidity can sometimes be a concern. Gold ETFs (Exchange-Traded Funds): These funds track gold prices and are traded on stock exchanges. They offer a convenient and liquid way to invest without dealing with physical gold. They typically have lower transaction costs compared to buying physical gold. Gold Mutual Funds: These invest in gold mining companies or gold-related assets. They offer exposure to gold without owning it directly and can generate returns through dividends and capital appreciation. Gold Futures and Options: These are derivatives that allow investors to speculate on future gold prices. They can provide significant leverage but carry high risk, making them suitable only for experienced investors. Digital Gold: This is a modern form of investment where investors can buy gold online in small quantities. It offers convenience and security without the need for physical storage. 3. Factors Influencing Gold Prices Gold prices are influenced by a combination of macroeconomic, geopolitical, and market-specific factors. Understanding these drivers can help investors make informed decisions: Inflation and Interest Rates: Gold is often inversely related to interest rates. When real interest rates (adjusted for inflation) are low or negative, gold becomes more attractive, driving up prices. Currency Movements: Gold is priced in US dollars globally. A weaker dollar makes gold cheaper for other currency holders, often increasing demand. Conversely, a stronger dollar can suppress gold prices. Geopolitical Risks: Wars, conflicts, and political instability can increase demand for gold as a safe-haven asset. Central Bank Policies: Central banks around the world hold significant gold reserves. Changes in their buying or selling behavior can impact global prices. Supply and Demand: Gold mining production, recycling, and industrial demand (especially in jewelry and technology) influence supply and demand dynamics. 4. Benefits of Investing in Gold Investing in gold provides multiple advantages: Wealth Preservation: Gold has historically maintained its value over centuries, protecting investors from currency depreciation and economic downturns. Portfolio Diversification: It reduces overall portfolio risk due to its low correlation with stocks and bonds. Liquidity: Gold is globally recognized and can be quickly sold or exchanged for cash in most markets. Inflation Hedge: Gold tends to retain purchasing power during periods of rising prices. Safe Haven During Crises: It is considered a stable investment during financial and geopolitical turmoil. 5. Risks of Investing in Gold Despite its advantages, gold investment carries certain risks: Price Volatility: Although gold is less volatile than stocks, it can still experience short-term price fluctuations due to market sentiment or speculative activity. No Income Generation: Unlike stocks or bonds, gold does not provide dividends or interest. Returns depend solely on price appreciation. Storage and Security Concerns: Physical gold requires secure storage and insurance, which can incur additional costs. Market Timing Risk: Buying gold at a peak can result in temporary losses if prices decline before an investor exits. 6. Strategies for Investing in Gold Successful gold investment requires careful planning and strategy: Long-Term Investment: Investors seeking stability can buy and hold gold for the long term to hedge against inflation and economic uncertainty. Diversification: Allocate a portion of the portfolio to gold alongside equities, bonds, and real estate to balance risk. Many advisors recommend 5–15% of a portfolio in gold. Dollar-Cost Averaging: Buying gold in regular intervals, regardless of price, can mitigate the impact of short-term volatility. Monitoring Macroeconomic Trends: Keeping track of inflation rates, interest rates, currency movements, and geopolitical events can help in timing investments. Combining Physical and Paper Gold: A combination of physical gold for security and ETFs or mutual funds for liquidity can optimize returns while managing risks. 7. Conclusion Gold remains a timeless investment vehicle with unique advantages. It offers protection against inflation, acts as a hedge during economic and geopolitical instability, and provides diversification to investment portfolios. While gold does not generate income, its long-term value preservation and liquidity make it a preferred choice for conservative investors. Understanding the forms of gold investment, factors influencing its price, and implementing strategic approaches can help investors leverage gold effectively for wealth protection and growth. Whether through physical ownership, digital platforms, or financial instruments, gold remains an essential component of a balanced investment strategy. By carefully assessing individual financial goals, risk tolerance, and market conditions, investors can harness the enduring appeal of gold to safeguard and grow their wealth.

Historical Background The concept of credit ratings originated in the early 20th century. The first formal credit rating agencies were Moody’s (founded in 1909) and Standard & Poor’s (S&P) (with origins in 1860, evolving into S&P in 1941). Fitch Ratings, founded in 1913, also became a major player in the credit rating industry. Initially, these agencies focused on rating bonds and fixed-income instruments in the United States. Over time, their operations expanded globally, covering sovereign nations, multinational corporations, structured finance products, and emerging markets. Today, the "Big Three"—Moody’s, S&P, and Fitch—dominate global credit ratings, collectively controlling roughly 95% of the market. Purpose and Function Financial rating agencies serve several critical functions in global finance: Credit Risk Assessment: Agencies evaluate the likelihood that a borrower will default on obligations. Ratings range from high-grade (low risk) to junk (high risk), providing a snapshot of credit quality. Investor Guidance: Investors, particularly institutional ones, use ratings to make informed investment decisions. Many funds and pension plans have policies restricting investments to certain rating thresholds. Market Efficiency: Ratings reduce information asymmetry between borrowers and lenders. Investors can quickly gauge risk without conducting extensive internal research. Regulatory Role: Financial regulators often incorporate ratings into capital adequacy rules. Banks, insurance companies, and investment funds may need higher capital reserves when investing in lower-rated securities. Benchmarking and Pricing: Ratings influence borrowing costs. Higher-rated entities enjoy lower interest rates, while lower-rated issuers pay a premium for risk. Types of Ratings Financial rating agencies provide different types of ratings, depending on the instrument or entity being assessed: Sovereign Ratings: Assess a country's ability and willingness to repay debt. These ratings impact government bond yields and influence foreign investment flows. Examples: U.S. AAA rating by S&P or India’s BBB- rating by Fitch. Corporate Ratings: Evaluate corporations’ creditworthiness, often for bonds or long-term loans. These ratings reflect financial health, debt structure, profitability, and operational stability. Structured Finance Ratings: Include mortgage-backed securities (MBS), collateralized debt obligations (CDOs), and asset-backed securities (ABS). These complex instruments require detailed risk modeling. Municipal Ratings: Cover local government entities or projects, particularly in the U.S., affecting municipal bond markets. Short-Term Ratings: Assess liquidity and ability to meet short-term obligations, often for commercial paper and money market instruments. Rating Methodologies Agencies use a mix of quantitative and qualitative methods to assign ratings. Key factors include: Financial Ratios: Debt-to-equity ratio, interest coverage ratio, profitability, and liquidity. Economic Environment: Macro conditions, inflation rates, currency stability, and economic growth. Political Stability: For sovereign ratings, political risk, governance, and regulatory frameworks are crucial. Industry Analysis: Sectoral trends, competition, and market dynamics. Management Quality: Corporate governance, strategy, and operational competence. The resulting rating is expressed as a letter grade. For example, S&P uses AAA (highest quality) to D (default), with intermediate grades like AA+, BBB-, etc. Moody’s uses a numeric system combined with letters (e.g., A1, Baa3). Global Influence of Rating Agencies Credit rating agencies have a profound impact on global finance: Capital Flow Direction: Sovereign ratings influence foreign investment, with higher-rated countries attracting more capital. Interest Rates and Borrowing Costs: Ratings directly affect yields on bonds and the cost of capital. Financial Market Stability: Ratings changes can trigger large-scale portfolio reallocations, influencing stock and bond markets worldwide. Emerging Markets: Agencies heavily affect emerging economies, where a downgrade can sharply increase debt servicing costs and reduce investor confidence. Criticism and Controversies Despite their significance, rating agencies have faced substantial criticism: Conflict of Interest: Agencies are paid by the issuers they rate, creating potential bias. For example, during the 2008 financial crisis, they rated many subprime mortgage-backed securities as AAA, later revealed to be extremely risky. Procyclicality: Ratings can amplify financial cycles. Downgrades during crises may force asset sales, worsening liquidity problems. Opaque Methodologies: The complexity and lack of transparency in rating models, especially for structured finance products, make it difficult for external stakeholders to assess validity. Regulatory Overreliance: Banks and investors often rely heavily on ratings for compliance, sometimes ignoring independent analysis, which can exacerbate financial instability. Market Concentration: The dominance of the Big Three limits competition, potentially reducing innovation and accuracy in risk assessment. Reforms and Modern Trends In response to criticism, rating agencies have evolved: Increased Transparency: Agencies now publish methodologies, criteria, and assumptions used in ratings. Regulatory Oversight: Post-2008 reforms, such as the Dodd-Frank Act in the U.S. and EU regulation, increased oversight to reduce conflicts of interest. Emergence of Alternatives: New players like DBRS Morningstar, Scope Ratings, and China Chengxin provide alternatives to the Big Three. Integration of ESG Factors: Many agencies now incorporate environmental, social, and governance (ESG) metrics, reflecting long-term sustainability risks. Technology and Big Data: Advanced analytics, machine learning, and real-time data improve predictive accuracy for ratings. Regional and Global Perspectives United States: The U.S. remains the center of rating agency operations, with S&P, Moody’s, and Fitch headquartered there. U.S. ratings influence global capital markets due to the dollar’s reserve currency status. Europe: European regulators have attempted to encourage competition, with agencies like Scope Ratings (Germany) and Creditreform Rating gaining traction. Asia: Emerging economies like China, India, and Japan have local agencies (e.g., China Chengxin, CRISIL, Japan Credit Rating Agency) to supplement international ratings. Global Coordination: International bodies like the International Organization of Securities Commissions (IOSCO) set principles for credit rating agencies to enhance reliability and transparency globally. Conclusion World finance rating agencies play a critical role in shaping global financial markets. Their ratings guide investor behavior, influence borrowing costs, and contribute to market efficiency. However, their dominance and occasional lapses in judgment highlight the need for careful oversight, transparency, and the integration of alternative perspectives. The evolution toward ESG considerations, technological adoption, and regional diversification suggests that rating agencies will continue to adapt to the complex demands of modern global finance. While their influence is undeniable, investors and policymakers must balance reliance on ratings with independent analysis and prudent risk management. The interplay between these agencies, global capital markets, and regulatory frameworks ensures that they will remain central players in international finance for decades to come.

1. Nature of Oil Market Volatility Oil is a commodity with characteristics that make it inherently volatile. Unlike many other goods, its supply and demand are sensitive to a wide array of factors including geopolitical events, macroeconomic conditions, technological changes, and environmental policies. Volatility in the oil market is typically measured using statistical methods, such as standard deviation of price returns, implied volatility from futures options, or historical price ranges. High volatility reflects uncertainty in market fundamentals and can manifest as sudden and large price swings over short periods. Historically, oil prices have experienced extreme fluctuations. For instance, the 1973 oil embargo led to a fourfold increase in crude oil prices, while the 2020 COVID-19 pandemic triggered a historic collapse in oil demand, causing oil futures to briefly turn negative in April 2020. These examples demonstrate the susceptibility of the market to both supply shocks and demand shocks. 2. Key Drivers of Oil Market Volatility a. Geopolitical Events Oil is highly concentrated in politically sensitive regions such as the Middle East, North Africa, and parts of South America. Conflicts, wars, sanctions, and political instability in these regions can significantly disrupt supply, creating volatility. For instance, tensions between Iran and the United States or conflicts in Libya have historically led to sudden spikes in crude oil prices due to fears of supply shortages. b. Supply and Production Shocks The oil market is influenced heavily by the production decisions of major oil producers, particularly the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) and its allies (OPEC+). Decisions to cut or increase production can create short-term price fluctuations. Unexpected supply disruptions, such as hurricanes affecting Gulf of Mexico oil production or sabotage of pipelines, also contribute to volatility. c. Demand Fluctuations Global demand for oil is sensitive to macroeconomic conditions. Economic recessions, changes in industrial activity, or shifts in transportation patterns can drastically alter demand. For instance, the 2008 global financial crisis led to a sharp decline in oil consumption, causing prices to drop from over $140 per barrel to below $40 per barrel within months. d. Financial Market Speculation Oil markets are not only physical commodity markets but also financial markets. Speculators and institutional investors trading oil futures and options amplify price swings. Large inflows of capital into oil derivatives can exacerbate volatility, particularly when market participants react to news or market sentiment rather than fundamentals. e. Technological and Structural Factors Technological developments, such as fracking and deepwater drilling, have changed the supply dynamics of oil markets, particularly in the United States. These innovations can increase supply flexibility but also create periods of oversupply, contributing to price volatility. Additionally, structural factors like the capacity of strategic petroleum reserves and pipeline infrastructure influence the market’s ability to absorb shocks. f. Currency Fluctuations Since oil is priced in U.S. dollars, changes in the dollar’s exchange rate affect global oil prices. A stronger dollar tends to make oil more expensive in other currencies, potentially reducing demand, while a weaker dollar can boost demand and price. These currency dynamics often contribute to short-term volatility. 3. Impacts of Oil Market Volatility a. Economic Implications Volatility in oil prices directly affects inflation, production costs, and economic growth. Rising oil prices increase costs for transportation, manufacturing, and energy-intensive industries, leading to inflationary pressures. Conversely, falling oil prices can depress revenues for oil-exporting countries and oil-related industries, potentially slowing economic growth. b. Corporate and Financial Implications Companies operating in oil-intensive sectors, such as airlines, shipping, and petrochemicals, are highly exposed to price swings. Volatile oil prices complicate budgeting, hedging strategies, and investment planning. For financial markets, oil price swings influence equities, bonds, and currency markets, creating ripple effects across the global financial system. c. Geopolitical and Strategic Implications Oil market volatility can influence international relations and policy decisions. Countries heavily dependent on oil revenues, such as Saudi Arabia, Russia, and Venezuela, are vulnerable to price swings, which can affect domestic stability and foreign policy. For energy-importing nations, volatile oil prices can impact trade balances and energy security strategies. d. Social and Environmental Implications High oil price volatility can impact living costs, particularly for households dependent on fuel and transportation. This can lead to social unrest, as seen in historical “fuel riots.” On the environmental front, volatility may either encourage energy conservation and renewables adoption during high prices or increase fossil fuel consumption during low-price periods. 4. Strategies to Manage Oil Market Volatility a. Hedging and Risk Management Companies and investors often use financial instruments like futures, options, and swaps to hedge against price fluctuations. For example, airlines may lock in fuel costs through hedging contracts to stabilize expenses. b. Diversification of Energy Sources Countries and companies aim to diversify energy sources to reduce dependency on volatile oil prices. This includes investing in renewable energy, nuclear power, and natural gas. c. Strategic Petroleum Reserves Governments maintain strategic reserves to buffer against supply disruptions. Releasing oil from reserves can stabilize prices temporarily during crises. d. Policy Measures Monetary and fiscal policies can influence oil demand and indirectly stabilize prices. Additionally, international cooperation through organizations like OPEC can moderate production to reduce extreme volatility. 5. Recent Trends in Oil Market Volatility In recent years, the oil market has experienced heightened volatility due to a combination of factors: COVID-19 Pandemic: The unprecedented collapse in global demand led to negative oil prices for the first time in history, reflecting extreme volatility. Energy Transition: The shift towards renewable energy and decarbonization policies introduces uncertainty about long-term demand for oil, influencing speculative behavior. Geopolitical Tensions: Conflicts in the Middle East, sanctions on Russia, and geopolitical rivalries continue to create price swings. Technological Disruption: The U.S. shale boom has added a flexible supply source, making the market more reactive to short-term demand changes. Macroeconomic Volatility: Inflation, interest rate changes, and currency fluctuations add layers of uncertainty to oil pricing. 6. Conclusion Oil market volatility is a multifaceted phenomenon driven by geopolitical, economic, financial, technological, and environmental factors. Its implications extend far beyond energy markets, influencing global economic stability, corporate strategy, geopolitical relations, and social welfare. Managing this volatility requires a combination of financial hedging, strategic reserves, diversified energy sources, and international cooperation. As the world transitions toward renewable energy and as geopolitical uncertainties persist, oil market volatility is unlikely to disappear. Instead, it will evolve, with market participants needing to adapt to a more complex and interconnected energy landscape. Understanding the dynamics of oil price swings remains crucial for investors, policymakers, and businesses navigating the global economy.

The Crypto Market: Bitcoin, Ethereum, and Stablecoins

1. Bitcoin: The Pioneer and Digital Gold Bitcoin, launched in 2009 by the pseudonymous Satoshi Nakamoto, was the first cryptocurrency and remains the most well-known and widely adopted digital asset. It operates on a decentralized peer-to-peer network using blockchain technology, a public ledger that records all transactions transparently and immutably. Bitcoin’s primary innovation lies in its ability to facilitate trustless transactions without intermediaries such as banks or payment processors. Key Features of Bitcoin: Limited Supply: Bitcoin has a capped supply of 21 million coins, which introduces scarcity, making it often referred to as “digital gold.” This scarcity underpins its appeal as a store of value, particularly during periods of fiat currency inflation. Decentralization: Bitcoin operates on a network of nodes worldwide. Its security and consensus mechanism, proof-of-work (PoW), ensures that no single entity controls the network, making it resistant to censorship and manipulation. Market Influence: Bitcoin often sets the tone for the broader crypto market. Price movements in BTC frequently influence altcoins and overall market sentiment. Investment Appeal: Many investors view Bitcoin as a hedge against traditional financial market volatility. Institutional interest, including purchases by corporate treasuries and ETFs, has strengthened its legitimacy as an asset class. Despite its strengths, Bitcoin faces challenges such as energy-intensive mining, scalability issues, and high price volatility. Nevertheless, it remains a cornerstone of the crypto market and a key driver of adoption. 2. Ethereum: Beyond Currency to Smart Contracts Ethereum, introduced in 2015 by Vitalik Buterin, expanded the concept of cryptocurrency by introducing programmable blockchain functionality through smart contracts. While Bitcoin primarily serves as digital money, Ethereum provides a decentralized platform for developers to create decentralized applications (dApps) and tokens. Key Features of Ethereum: Smart Contracts: Ethereum enables self-executing contracts coded on the blockchain. These contracts automatically enforce the terms of agreements, reducing the need for intermediaries and enhancing transparency. Decentralized Finance (DeFi): Ethereum has become the backbone of the DeFi ecosystem, hosting platforms that offer lending, borrowing, yield farming, and decentralized exchanges. This innovation allows individuals to access financial services without relying on traditional banks. ERC-20 and Tokenization: Ethereum’s ERC-20 standard has facilitated the creation of numerous tokens, including stablecoins, utility tokens, and governance tokens. This tokenization has broadened the crypto ecosystem and investment opportunities. Ethereum 2.0 and Proof-of-Stake: The transition from proof-of-work to proof-of-stake (PoS) via Ethereum 2.0 aims to address energy consumption and scalability issues, improving transaction speeds and network sustainability. Ethereum’s flexibility and technological innovation have made it the second-largest cryptocurrency by market capitalization. It also plays a critical role in the broader crypto ecosystem by powering DeFi, NFTs, and enterprise blockchain solutions. 3. Stablecoins: Bridging Crypto and Traditional Finance Stablecoins are digital assets designed to maintain a stable value, usually pegged to fiat currencies such as the U.S. dollar. Unlike Bitcoin and Ethereum, stablecoins are not primarily intended as speculative investments but as mediums of exchange, liquidity instruments, and hedges against volatility. Examples include Tether (USDT), USD Coin (USDC), and Binance USD (BUSD). Key Features of Stablecoins: Price Stability: By pegging their value to stable assets, stablecoins mitigate the extreme volatility seen in cryptocurrencies like BTC and ETH, making them suitable for payments, remittances, and trading. Utility in Crypto Markets: Traders often use stablecoins to enter or exit positions without converting to fiat currency. They provide liquidity across exchanges and facilitate decentralized finance activities. Types of Stablecoins: Fiat-collateralized: Backed 1:1 by fiat reserves (e.g., USDC, USDT). Crypto-collateralized: Backed by other cryptocurrencies held in smart contracts (e.g., DAI). Algorithmic: Value maintained through algorithms and smart contracts without direct collateral (e.g., TerraUSD before its collapse). Risks and Regulatory Attention: Despite their stability, stablecoins carry risks, including reserve transparency, regulatory scrutiny, and the potential for de-pegging in stressed market conditions. Regulators worldwide are increasingly focusing on stablecoin issuance and management to ensure financial stability. Stablecoins serve as a bridge between traditional finance and crypto markets, enabling fast, low-cost, and borderless transactions, which enhance crypto adoption in real-world applications. 4. Market Dynamics and Interconnections The crypto market is interconnected, with Bitcoin, Ethereum, and stablecoins each influencing market behavior differently. Bitcoin’s dominance often dictates overall market sentiment, while Ethereum drives innovation and new market segments, particularly DeFi and NFTs. Stablecoins provide liquidity and stability, acting as a buffer during periods of market volatility. Market Drivers: Institutional Participation: Increasing interest from hedge funds, asset managers, and corporations has introduced liquidity and legitimacy, particularly in Bitcoin and Ethereum. Regulatory Environment: Policy decisions impact crypto prices, adoption, and innovation. Countries with clear crypto regulations foster growth, while regulatory uncertainty can trigger volatility. Technological Innovation: Upgrades such as Ethereum 2.0, layer-2 scaling solutions, and Bitcoin’s Lightning Network enhance usability and adoption. Global Macroeconomic Factors: Inflation, interest rates, and geopolitical events influence crypto markets similarly to traditional assets, but the decentralized nature of cryptocurrencies often creates unique correlations and behaviors. 5. Risks and Considerations While cryptocurrencies offer high returns and innovation, they also carry significant risks: Volatility: Prices can fluctuate dramatically in short periods, impacting investments and trading strategies. Regulatory Uncertainty: Governments are actively formulating policies to address taxation, securities laws, and stablecoin usage. Security Risks: Hacks, scams, and smart contract vulnerabilities pose substantial threats to investors and platforms. Market Manipulation: Large holders, known as whales, can influence prices, particularly in low-liquidity markets. Environmental Concerns: Energy-intensive PoW networks like Bitcoin have raised environmental sustainability questions. Understanding these risks is essential for informed participation and risk management in the crypto market. 6. Future Outlook The future of the crypto market is promising yet uncertain. Key trends shaping the next phase include: Integration with Traditional Finance: Cryptocurrencies and blockchain-based financial services are increasingly integrated with banks, payment providers, and investment platforms. Decentralized Finance Expansion: Ethereum and other smart-contract platforms are expected to drive further DeFi adoption, enhancing financial inclusion. Central Bank Digital Currencies (CBDCs): Governments exploring digital currencies may coexist or compete with stablecoins, influencing the market structure. Technological Advancements: Layer-2 solutions, sharding, and interoperability protocols may improve scalability, reduce fees, and enhance user experience. Institutional Adoption: Continued involvement of institutional investors may stabilize markets and provide legitimacy, driving wider adoption. The evolution of Bitcoin, Ethereum, and stablecoins indicates a maturing market that balances speculative potential with practical financial applications. Conclusion The cryptocurrency market, anchored by Bitcoin, Ethereum, and stablecoins, represents a transformative shift in global finance. Bitcoin provides a decentralized store of value, Ethereum enables programmable finance and smart contracts, and stablecoins bridge traditional finance and the crypto world. While the market offers substantial opportunities, it also carries risks from volatility, regulation, and technology. Understanding these three pillars of crypto is essential for navigating the market’s complexities, fostering adoption, and leveraging the innovations that cryptocurrencies bring to the global financial landscape. The interplay between these assets continues to shape the evolution of digital finance, reflecting both the opportunities and challenges of a decentralized financial future.

The Scope and Importance of International Policy Analysis The importance of international policy analysis has grown significantly in the 21st century due to globalization, technological advancements, and complex interdependence among states. Policies addressing climate change, trade, health crises, cybersecurity, and conflict resolution have far-reaching consequences that transcend national boundaries. Analysts in this field aim to evaluate not only the effectiveness of policies but also their ethical, political, economic, and social implications. International policy analysis provides policymakers and stakeholders with evidence-based insights that inform decision-making. It facilitates the identification of potential risks, benefits, and trade-offs associated with different policy options. In an increasingly interconnected world, where actions in one country can ripple globally, the role of international policy analysis is indispensable for promoting cooperation, reducing conflicts, and fostering sustainable development. Key Theoretical Approaches Several theoretical frameworks guide international policy analysis, providing structured ways to interpret complex global interactions: Realism: Rooted in political science, realism emphasizes the pursuit of national interest and power in an anarchic international system. Policy analysts using this approach focus on how states prioritize security, military strength, and strategic alliances. Realism is often applied in analyzing defense, security, and geopolitical policies. Liberalism: Liberal theories highlight cooperation, institutions, and the role of international law. From this perspective, policy analysis examines how international organizations, treaties, and multilateral agreements influence global outcomes. Liberalism is particularly relevant in trade policy, human rights, and environmental governance. Constructivism: Constructivist approaches stress the importance of ideas, norms, and identities. Analysts study how perceptions, cultural factors, and social norms shape policy decisions, highlighting that international relations are not merely dictated by material interests but also by shared understandings. Critical and Postcolonial Theories: These approaches challenge mainstream perspectives, focusing on power imbalances, historical legacies, and structural inequalities. They analyze how global policies can perpetuate economic or political dominance and often emphasize marginalized voices in global governance. Methodologies in International Policy Analysis International policy analysis employs a wide range of methodologies to assess policy effectiveness and implications: Qualitative Analysis: This involves the study of policy documents, treaties, speeches, and case studies. Interviews with policymakers and experts provide insights into decision-making processes and political dynamics. Qualitative approaches are essential for understanding the motivations, ideologies, and negotiations behind international policies. Quantitative Analysis: Analysts use statistical models, economic indicators, and large datasets to evaluate the outcomes of international policies. Quantitative approaches are particularly useful for assessing trade agreements, development aid effectiveness, and economic sanctions. Comparative Analysis: By comparing policies across different countries or regions, analysts can identify best practices, common challenges, and potential solutions. Comparative studies help in understanding how varying political, economic, and cultural contexts influence policy outcomes. Scenario and Risk Analysis: This method projects potential future developments, assessing how current policies might perform under different global conditions. It is crucial for long-term planning in areas such as climate change, security threats, and technological advancements. Key Areas of Focus Global Security and Defense Policy: Analysts examine issues like conflict prevention, peacekeeping, arms control, and counterterrorism. Understanding how states and international organizations manage security threats helps in designing effective policies that minimize the risk of conflict. International Trade and Economic Policy: Trade agreements, tariffs, foreign investment regulations, and economic sanctions are central to global economic governance. Policy analysis evaluates the impacts of these measures on economic growth, employment, inequality, and global markets. Environmental and Climate Policy: Climate change is a global challenge requiring coordinated policy responses. Analysts assess international treaties like the Paris Agreement, evaluate the effectiveness of carbon reduction strategies, and explore the economic and social implications of environmental policies. Global Health Policy: International policy analysis in health examines responses to pandemics, access to vaccines, and global health governance structures. Effective health policies require coordination between national governments, the World Health Organization, and other global health actors. Human Rights and Social Policy: Policies addressing human rights, migration, and humanitarian aid are evaluated to ensure compliance with international law and ethical standards. Analysis identifies gaps, implementation challenges, and the role of civil society in influencing policy outcomes. Challenges in International Policy Analysis Analyzing international policy presents unique challenges due to the complexity of global governance: Diverse Stakeholders: International policies often involve multiple actors with conflicting interests. Balancing these interests requires careful negotiation and strategic compromise. Data Limitations: Access to reliable and timely data across countries can be challenging. Analysts must often work with incomplete or biased information. Dynamic Global Context: International relations are fluid, influenced by economic shifts, technological change, and geopolitical tensions. Analysts must adapt their frameworks to account for rapid developments. Cultural and Normative Differences: Policies may have varying impacts in different cultural contexts, making universal policy prescriptions difficult. Impact and Applications International policy analysis plays a pivotal role in shaping global governance. It informs the strategies of governments, international organizations, and NGOs, guiding decisions in diplomacy, trade, security, and development. By identifying unintended consequences and proposing evidence-based alternatives, analysts contribute to more effective and ethical policymaking. Furthermore, international policy analysis fosters collaboration across borders. It helps build consensus on pressing global issues like climate change, human trafficking, and financial crises. By integrating insights from multiple disciplines, including economics, political science, sociology, and law, analysts provide comprehensive solutions that address both immediate challenges and long-term goals. Conclusion International policy analysis is an essential field in a world characterized by interconnectedness and complexity. It equips decision-makers with the knowledge and tools to navigate global challenges, promoting cooperation, stability, and sustainable development. By combining theoretical frameworks, methodological rigor, and practical insights, international policy analysis enhances our understanding of global governance and contributes to the creation of policies that are equitable, effective, and forward-looking. In an era of global crises—from pandemics and climate change to geopolitical conflicts—international policy analysis is not just an academic exercise; it is a vital instrument for shaping a more secure, just, and prosperous world.

Risk Psychology and Performance in Global Markets

1. Defining Risk Psychology Risk psychology, sometimes referred to as behavioral finance, examines how emotions, cognitive biases, and mental frameworks shape perceptions of risk and influence decision-making. Traditional economic theory assumes that market participants are rational actors who always make decisions based on complete information and logical analysis. However, decades of research, particularly by psychologists like Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky, have shown that human behavior often deviates from rationality. Traders may overreact to news, underestimate the probability of rare events, or follow herd behavior—actions that directly impact performance in global markets. Risk psychology can be divided into several key dimensions: Risk Perception: How individuals interpret and assess potential losses and gains. Risk Tolerance: The degree to which an individual or organization is willing to accept uncertainty or potential financial loss. Cognitive Biases: Systematic errors in thinking, such as overconfidence, anchoring, or confirmation bias. Emotional Responses: Reactions such as fear, greed, panic, or euphoria that can override logical decision-making. 2. Cognitive Biases and Market Behavior One of the central insights from risk psychology is that cognitive biases can significantly distort market performance. Some of the most influential biases include: Overconfidence: Traders often overestimate their knowledge or forecasting ability, leading to excessive risk-taking or frequent trading. In global markets, overconfident investors may underestimate geopolitical risks or macroeconomic uncertainties, which can result in large losses. Loss Aversion: This is the tendency to weigh potential losses more heavily than equivalent gains. In volatile markets, loss-averse behavior can lead investors to exit positions prematurely, missing potential recoveries. Herding: Many investors follow the actions of the majority rather than independent analysis, leading to bubbles and crashes. The 2008 global financial crisis and other market corrections illustrate how herding behavior amplifies systemic risk. Anchoring: Market participants often rely too heavily on a reference point, such as a stock's past high, when making decisions. This can lead to mispricing in fast-moving global markets. These biases illustrate that market performance is as much about managing internal psychological factors as it is about external economic conditions. Recognizing and mitigating these biases is essential for achieving consistent performance. 3. Emotional Drivers in Global Markets Emotions are another powerful factor affecting performance. Fear and greed are two dominant emotions influencing trading decisions: Fear: Sudden market downturns, geopolitical events, or economic crises can trigger fear, leading to panic selling. Fear-driven actions often exacerbate volatility and can result in substantial losses. Greed: Conversely, the desire for high returns can push investors into over-leveraged positions or speculative assets. Excessive greed may lead to ignoring warning signals, contributing to financial bubbles. In global markets, these emotions are amplified by the 24/7 nature of trading, high-speed information flow, and exposure to international geopolitical and macroeconomic events. Investors must develop emotional discipline to withstand market volatility and maintain long-term performance. 4. Risk Tolerance and Portfolio Management Risk psychology directly informs risk tolerance, which is crucial for portfolio construction and investment strategy. Understanding one’s own risk profile—or that of an organization—is essential for aligning investment choices with financial goals and market conditions. Conservative Investors: Prefer stable, low-risk assets even if returns are modest. They may underperform in bullish markets but avoid significant drawdowns during crises. Aggressive Investors: Willing to take on higher risk for the potential of greater returns. Their performance can be stellar in favorable conditions but highly volatile during downturns. Institutional Risk Management: Large global institutions often implement structured risk management frameworks that combine quantitative models with psychological insights to mitigate irrational decision-making among traders. Balancing risk tolerance with market opportunities is a core component of consistent performance. Investors who fail to match their strategies with their psychological profile often make impulsive decisions that negatively affect returns. 5. The Impact of Risk Psychology on Market Trends Risk psychology doesn’t just affect individual investors—it can influence global market trends. Collective human behavior, shaped by shared perceptions of risk and sentiment, can drive market cycles: Bull Markets: Optimism and reduced risk perception fuel buying, often inflating asset prices beyond fundamental values. Bear Markets: Pessimism and heightened fear lead to selling, creating sharp declines. Volatility Spikes: Emotional reactions to unexpected events, such as geopolitical crises or central bank announcements, can result in abrupt market swings. Market sentiment indicators, like the Volatility Index (VIX), are essentially measures of collective risk psychology. Traders and institutions often use these tools to gauge sentiment and anticipate potential market movements. 6. Strategies to Mitigate Psychological Risk Given the profound influence of risk psychology on performance, it is crucial for market participants to implement strategies to manage these effects: Education and Awareness: Understanding common biases and emotional triggers helps investors make more rational decisions. Structured Decision-Making: Using checklists, rules-based systems, and quantitative models reduces the influence of emotion on trading decisions. Diversification: Spreading investments across asset classes, geographies, and strategies mitigates the impact of unexpected events and reduces stress. Regular Reflection and Journaling: Tracking decisions, outcomes, and emotional states helps identify patterns and improve future performance. Stress Testing: Simulating adverse scenarios allows traders and institutions to anticipate emotional responses and refine risk management. 7. Conclusion Performance in global markets is a complex interplay of economic fundamentals, technical analysis, and, importantly, human psychology. Risk psychology illuminates the ways in which emotions, cognitive biases, and perception of uncertainty influence market behavior. Traders and investors who cultivate self-awareness, emotional discipline, and structured decision-making frameworks can navigate market volatility more effectively and improve long-term performance. Global markets are inherently uncertain, and even the most sophisticated models cannot fully predict outcomes. By understanding risk psychology, market participants gain a powerful tool: insight into their own behavior and the collective behavior of others. This understanding not only enhances individual performance but also contributes to a more stable and resilient financial system. In essence, mastering risk psychology is not about eliminating risk—it’s about managing human responses to risk, aligning decisions with long-term goals, and leveraging an understanding of human behavior to thrive in the complex world of global finance.

Disclaimer

Any content and materials included in Finbeet's website and official communication channels are a compilation of personal opinions and analyses and are not binding. They do not constitute any recommendation for buying, selling, entering or exiting the stock market and cryptocurrency market. Also, all news and analyses included in the website and channels are merely republished information from official and unofficial domestic and foreign sources, and it is obvious that users of the said content are responsible for following up and ensuring the authenticity and accuracy of the materials. Therefore, while disclaiming responsibility, it is declared that the responsibility for any decision-making, action, and potential profit and loss in the capital market and cryptocurrency market lies with the trader.